Findings and Methodology

Avaaz recently conducted a two-day experiment (from October 6-7, 2021) to understand if and how Instagram’s algorithm pushes young users toward potentially harmful eating disorder-related content.

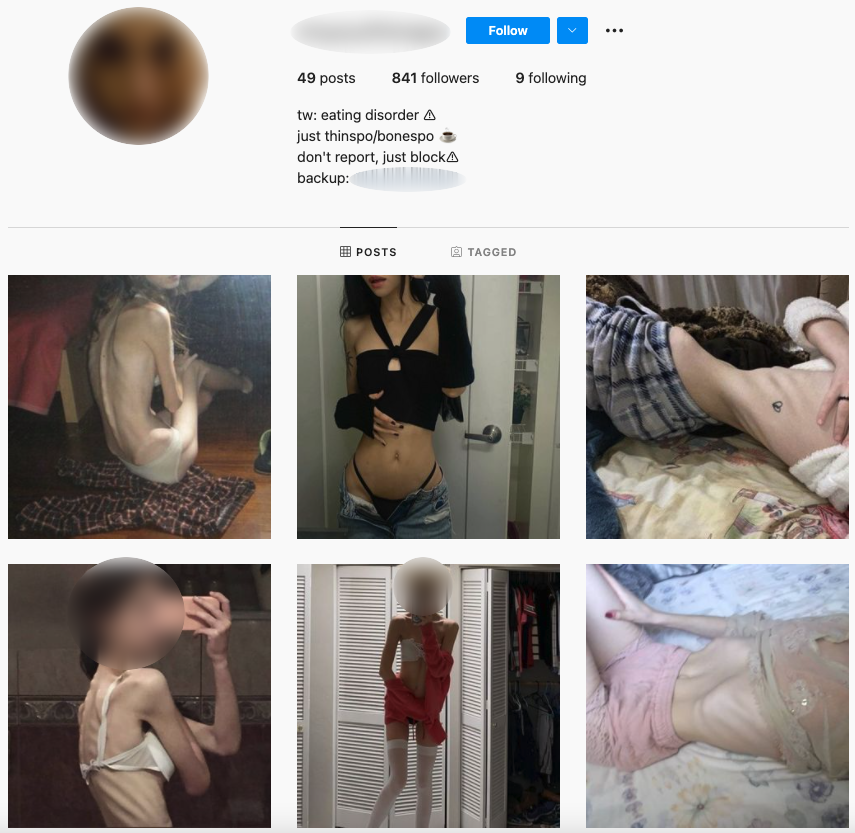

Our research indicates that finding Instagram profiles with potentially harmful and triggering eating disorder-related content is as easy as searching for #anorexia

2

, and that Instagram’s “suggestion” algorithm can continue to push users further and further into the world of such content through suggesting a seemingly endless stream of “related” profiles. This is despite Instagram’s

stated

ban on content that “promotes, encourages, coordinates, or provides instructions for eating disorders”, as well as their

policy

that certain “triggering” posts about eating disorders -- even if they are not actively encouraging them -- “may not be eligible for recommendations” because it “impedes our [Instagram’s] ability to foster a safe community.

3

For this research, Avaaz created a brand new Instagram account registered as a 17-year-old (gender unspecified). After searching for #anorexia, Instagram suggested different posts associated with the hashtag.

4

Our team quickly found a profile that had shared a photo of a very thin body, whose bio said: “Ed, thinspo” (meaning “eating disorder” and “thinspiration”, a commonly used

term

among those “who have identified eating disorders as a lifestyle choice, rather than an illness”).

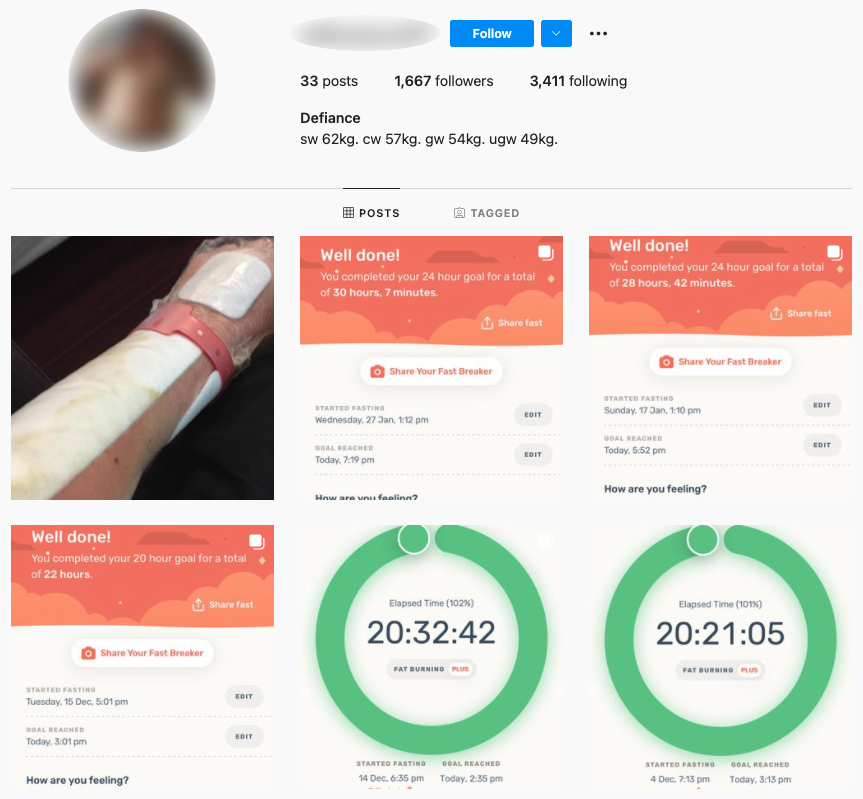

Avaaz followed that profile, and from there Instagram fed our account more and more profiles that shared potentially harmful and triggering content, including extreme dieting, behaviors like binging and purging, photos of very thin or emaciated people, descriptions of self-harm, “current weights” versus “goal weights”, and “accountability” posts that promised to fast or exercise in exchange for likes and comments.

Over the course of two days

5

following these types of profiles, our team uncovered some additional troubling elements about Instagram’s suggestion algorithm, notably that it suggested

private user profiles

to follow as well as

profiles seemingly belonging to minors

.

6

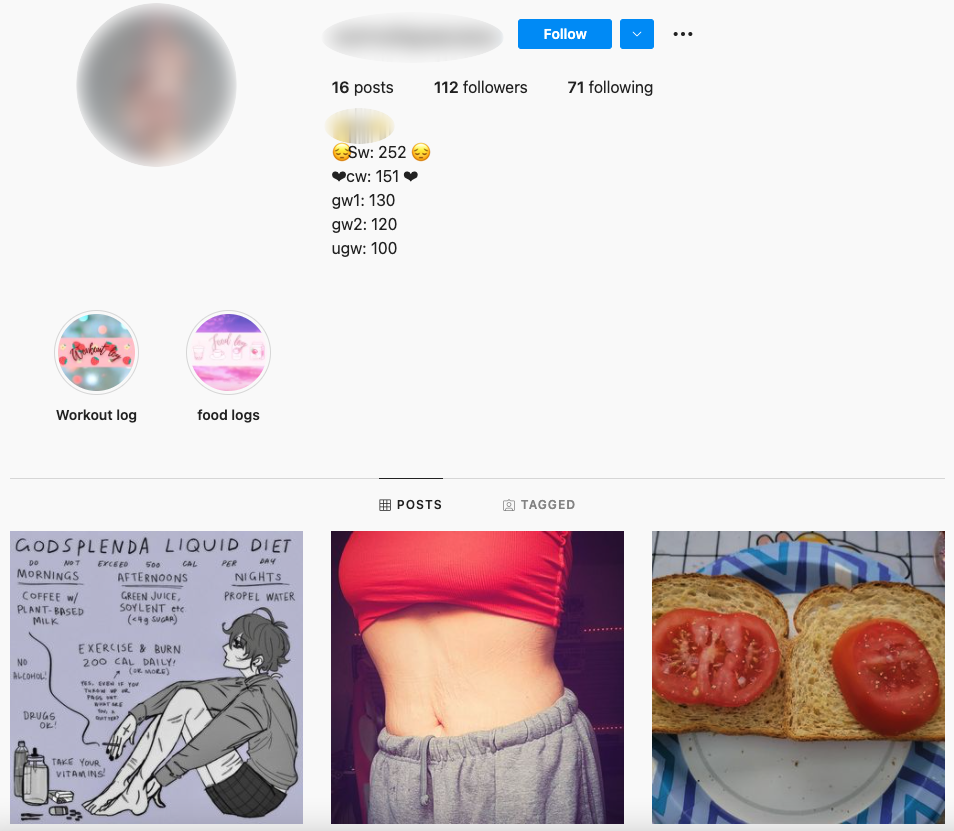

While Avaaz could not see the posts of private user profiles, our threshold for including these in our dataset was based on explicit or coded language used in their publicly available bios that strongly indicated their posts may contain potentially harmful and triggering content. Such bios often included terms like “CM/GW/UGW” (current weight, goal weight, ultimate goal weight) or “TW ED/ANA/MIA/SH” (trigger warning eating disorder, anorexia, bulimia, self-harm) -- acronyms that experts have

documented

as commonly used by people both suffering from or promoting eating disorder behaviors.

In total,

Avaaz documented

:

-

153 recommended profiles with a combined 94,762 followers7

whose bios and/or posts contained harmful eating disorder-related content;

-

The majority (66%) of recommended profiles were private

(101 out of 153), while only 34% were public (52 out of 153);

-

12 recommended profiles appeared to belong to minors

under the age of 18;

-

The majority (85%) of recommended profiles were “small accounts”

with fewer than 1,000 followers. Of these, 25% had fewer than 100 followers.

Avaaz’s work follows the recent

research

and findings of Senator Richard Blumenthal’s team, whose Instagram account registered as a 13-year-old girl was increasingly fed more and more extreme dieting accounts by the Instagram algorithm over time, after initially following some dieting and pro-eating disorder accounts.

Our combined research indicates that Instagram has not thoroughly investigated and addressed in earnest how its algorithm feeds potentially harmful and triggering eating disorder content to young users.

To the contrary, its algorithm has learned to associate triggering and at times quite graphic profiles with one another and push them to young users to follow, even if those profiles are private and/or seemingly belong to minors. This puts certain demographics of users at increased risk for self-harm, as eating disorder experts have reported that such content

can

“act as validation for users already predisposed to unhealthy behaviors.”

Tell Your Friends