Section 1: Facebook puts harmful wildlife trafficking content at users’ fingertips in just a few clicks

In just two days, Avaaz researchers collected 129 posts containing potentially harmful wildlife trafficking content.

This content consisted of posts seeking to buy or sell species listed in Appendix I or II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (

CITES

), an international agreement that aims to ensure that international trade does not threaten the survival of species of wild animals and plants. Species

listed

in

Appendix I

of CITES are those currently threatened with extinction and species listed in

Appendix II

are at risk of becoming threatened with extinction if trade is not closely controlled –

in other words,

“species about which, based on international agreement, there is reason to be concerned” and the

trade

of which should be either prohibited or subject to strict rules and conditions.

Despite the internationally recognized and agreed need to protect these species, researchers were able to find 129 posts in a matter of clicks, using the Facebook search bar. Researchers had no previous investigative knowledge of wildlife trafficking, therefore their experience demonstrates

how easy it is for average users to access potentially harmful wildlife trafficking content through Facebook’s platform.

Furthermore,

Facebook removed just 43% of posts

containing potentially harmful wildlife trafficking content after these were reported by researchers using Facebook’s ‘Report post’ tool,

evidencing a clear need to improve its moderation efforts.

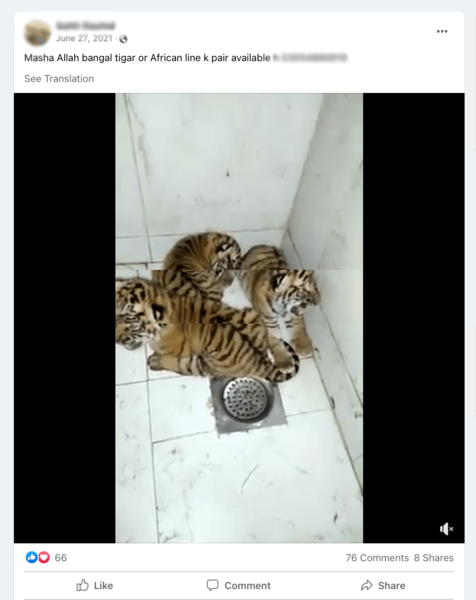

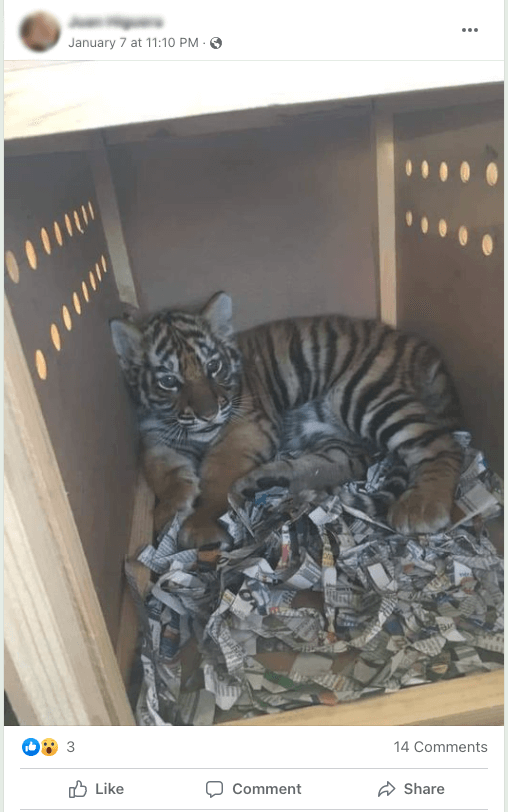

Example 1: Tiger cubs

This

advertisement for tiger cubs

was posted to a public group on Facebook in June 2021. Tigers are

listed

in Appendix I of CITES. They are considered to be endangered, with just

3,900

estimated to be left in the wild.

WWF

identifies commercial captive tiger breeding as a “significant obstacle to the recovery and protection of wild tiger populations because they perpetuate the demand for tiger products, serve as a cover for illegal trade and undermine enforcement efforts.”

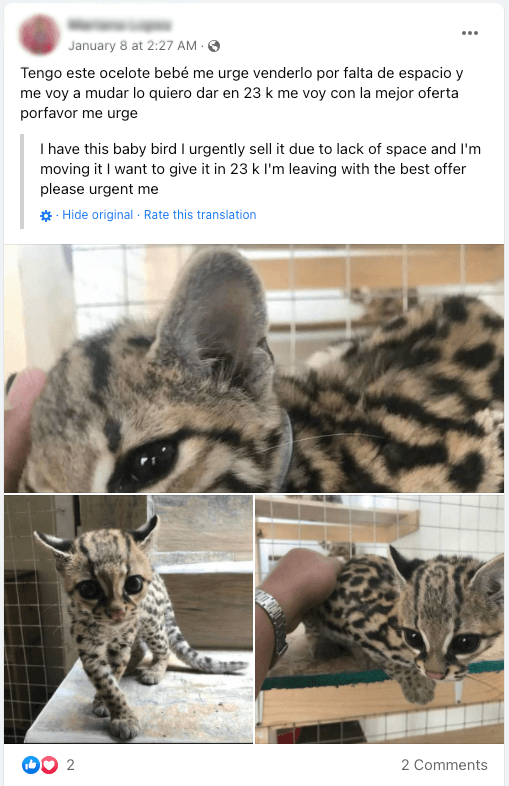

Example 2: African gray parrot

In the post above,

a seller states that an African gray parrot is available for “rehoming”

– a code

often

used by traffickers to indicate that an animal is for sale, confirmed on this post by prospective buyers asking for a price. African gray parrots are

listed

in Appendix I of CITES.

Sociable

and highly intelligent, African gray parrots are one of the

most popular

pet birds in the world. Their friendly nature also makes them

easy targets

for poachers. The high demand for African gray parrots, in conjunction with habitat loss, is

pushing

the species towards extinction. They have been

marked

as endangered on the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species.

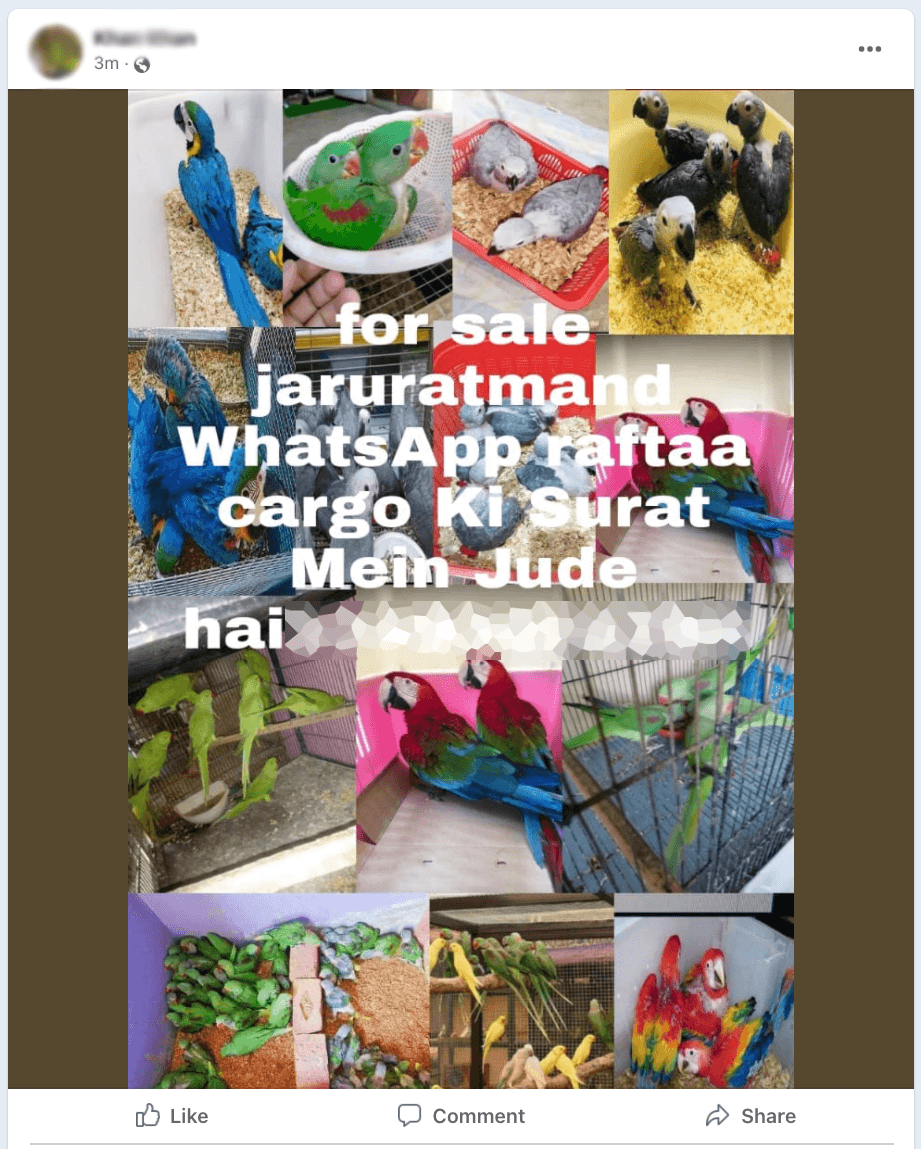

Example 3: Pangolins and rhino horn

This post, found on

a Facebook page

that specializes in the trade and export of “Pangolin Scales & Rhino Horn to Vietnam, China, Hongkong, Malaysia, Singapore from Africa,”

puts out a call for bidders on their animals and products.

Pangolins are a

CITES Appendix I species.

Despite the CITES

ban

on international commercial pangolin trading, which entered into force in 2017, pangolins are the

most trafficked mammals in the world.

They are trafficked most often for their

meat and scales,

which are used in traditional medicine and leather products. This trade directly threatens pangolin survival – all eight species of pangolin are

protected

under national and international laws, and two are critically endangered.

Similarly, international trade in rhino horn is

illegal

under CITES, but high demand for rhino horn in Asia leads to the poaching of three rhinos per day on average in South Africa alone. Black rhinos, a main target for poachers, are critically

endangered,

with only 5,600 left in the wild.

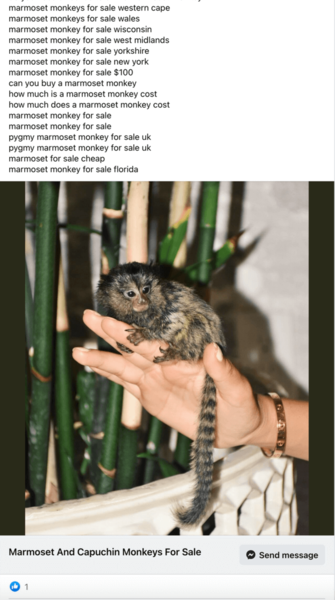

Example 4: Marmoset monkey

Posted on a page titled ‘Marmoset And Capuchin Monkeys For Sale’, this post features

a photo of a pygmy marmoset under a list of keywords meant to attract potential buyers in various countries.

Pygmy marmosets are

listed

on CITES Appendix II.

Native

to the Amazon region, pygmy marmosets are among the

smallest primates,

with adults weighing just

four ounces

when mature. They are often

sought

as pets for their size and appearance. For this reason, the pet trade is the largest threat to this species’ survival – they are increasingly threatened by

international demand

for so-called ‘thumb monkeys.’

Tell Your Friends